‘When there’s no more room in hell the dead will walk the earth’

Dawn of the Dead is a 1978 American zombie horror film written and directed by George A. Romero. It was the second film made in Romero’s Living Dead series but contains no characters or settings from his seminal 1968 breakthrough Night of the Living Dead, and shows on a larger scale the zombie plague’s apocalyptic effects on society.

The movie stars David Emge (Basket Case 2, Hellmaster), Ken Foree (Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre 3, The Devil’s Rejects), Scott Reiniger (Knightriders) and Gaylen Ross (Creepshow).

Plot:

The chaotic WGON television newsroom is attempting to make sense of the evidently widespread phenomenon of the dead returning to life to eat the living. Their main efforts are focused on simply staying on air to act as a public information system for those still alive to find places to shelter.

Meanwhile, outside tensions have erupted at a tenement building where the residents are refusing to hand over the dead bodies of their loved ones to the authorities for them to dispose of, resulting in a SWAT team assembling to resolve the issue by force. As both sides incur casualties at their own hands and those of the reanimated corpses, four bystanders gravitate towards each other and plot to escape this madness; SWAT soldiers Roger (Reiniger) and Peter (Foree) and a couple who work at the station, Francine (Ross) and Stephen (Emge) – it is agreed that they will take the company’s helicopter and seek sanctuary.

As both sides incur casualties at their own hands and those of the reanimated corpses, four bystanders gravitate towards each other and plot to escape this madness; SWAT soldiers Roger (Reiniger) and Peter (Foree) and a couple who work at the station, Francine (Ross) and Stephen (Emge) – it is agreed that they will take the company’s helicopter and seek sanctuary.

With the helicopter liberated, they stop off for fuel, narrowly avoiding the attention of both zombie adults and children – on a human angle, it is clear the soldiers come from very different worlds to Fran and Stephen.

Still short of fuel, they set off again and happen upon a shopping mall – though surrounded by the living dead, the opportunity presented by an abundance of food and provisions, as well as a place to the secrete themselves is irresistible.

Devising a system of clearing the zombies already in the mall, during which Roger is bitten but survives, and creating their own living quarters behind a false wall, they learn (Stephen included) that Fran is four months pregnant. Roger and Peter are keen to look for other survivors but under the circumstances, the others feel that staying put and essentially quitting whilst they’re ahead would be the safest option.

The images they witness on their looted television give little hope but before a decision can be agreed upon, they realise that the mall has also attracted the attention of an army of local bikers, not looking for anything except target practice and goods. Their defences breached, the foursome faces a seemingly impossible situation where both human and zombie foes have designs on their hides. Can they reclaim the mall or get to the helicopter before they find themselves wandering the mall for eternity?

Our review:

Although in gestation for some years before making it to the screen, the follow-up to Romero’s seminal Night of the Living Dead appeared a full ten years later.

The slow-burn effect of this film, plus George’s notoriously poor grasp of finances led to producer Richard Rubinstein looking further afield for investment to get the project off the ground. Salvation came in the form of the genius Italian film director, Dario Argento (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage; Deep Red; Suspiria) who had long admired Night and could see the value in producing a sequel of some kind.

And so began an arrangement whereby the funds were made available to make the film in exchange for international distribution rights and Argento’s option to make an entirely different cut of the film for a Continental audience. Romero ensconced himself in a small apartment in Rome where he quickly wrote the screenplay, allowing for filming to begin in Pennsylvania in November 1977.

The key to Romero’s vision for the film was the iconic mall setting, already firmly imprinted in his mind due to the owners of the Monroeville Mall, east of Pittsburgh, in existence since 1969 and one of the first really large out of town shopping districts. His connections were enough for the owners, Oxford Development, to allow out-of-hours filming. Romero had been given a private tour of the facility and was privy to sealed off areas which had been stocked with civil

Romero’s personal connections were enough for the owners, Oxford Development, to allow out-of-hours filming. The director had been given a private tour of the facility and was privy to sealed off areas which had been stocked with civil defence equipment in case of a National emergency – a fact fully exploited in the film.

Casting for the film was the responsibility of John Amplas (star of Romero’s Martin and later Day of the Dead) who also has a small role of a Mexican, shot by the SWAT team in the early exchange of fire. The cast was made up of largely local actors who had featured in theatre rather than film roles – indeed few of them went on to have significant film careers but still trod the boards at provincial theatres.

Friends and acquaintances were coerced into appearing, amongst their number, George’s wife and assistant director, Christine Forrest (also appearing in several other of his films in an acting capacity, including Martin and Monkey Shines) George himself (seated alongside her in the TV studio sequence), Pasquale Buba (later to edit the likes of Day of the Dead and Stepfather 2), special effects guru Tom Savini and Joe Pilato (Day of the Dead‘s Rhodes).

Buy Blu-ray: Amazon.com

Such economy and camaraderie were to pay off spectacularly. Even minor characters are given hinted-at histories which are endlessly intriguing – and eye-patched Doctor Millard Rausch (Richard France) opines thoughtfully on television: “These creatures cannot be considered human… they must be destroyed on sight! … Why don’t we drop bombs on all the big cities?”

Filming at the mall could hardly have commenced at a more inconvenient time, the freezing cold temperatures and busy festive season meaning that shooting times were extremely tight (between 10.00 pm and 8.00 am), resulting in several occasions when members of the public were forced to consider why their shopping trip looked more like a ghoul-infested abattoir.

Exterior shots were even harder to come by, only half a day a week was allotted to get the shots of the swarms of zombies roaming the car park, without pesky customers getting in the shot. Scenes such as mall breakers revelling in the local bank’s bundles of notes necessitated a great deal of care to ensure light-fingered crew members didn’t make off with the ‘props’.

The most familiar location in the mall, JC Penney’s department store, has since closed, though the mall remains, in a surprisingly familiar state (see pics below). Other locations employed, such as the abandoned airfield, the gun store, and the quartet’s hideout, were shot locally too, the latter being constructed in Romero’s production offices, Laurel.

Make-up and special effects were the responsibility of Tom Savini and team, also including Gary Zeller and Don Berry, who later both worked on such films as Scanners and Visiting Hours. Having already developed his talents on Deranged and Martin, Savini was far from an enthusiastic amateur, though it was this film and the free reign Romero gave him, that helped establish his name as the go-to for gore effects for many years to come.

Signature effects on Dawn include the flat-headed zombie being semi-decapitated by helicopter blades (a ludicrously dangerous effect involving an admittedly obviously fake headpiece) and the exploding head in the tenement sequence (so redolent of a similar effect in Scanners) by shooting fake heads packed with condoms filled with fake blood and scraps of food.

One bone of contention with many is the unrealistic blue/grey make-up the zombie’s sport, a mile away from the wonderfully decaying cadavers of, for example, the 1979 Lucio Fulci directed Italian cash-in Zombie Flesh Eaters. Romero has ‘validated’ this by claiming it was always his aim to have a comic-book feel to the film, though this smacks slightly of convenience. What is true is that the never-redder blood is a real eye-opener and lends itself to large-screen viewing. What the zombies lack in biological realism, they certainly gain in back story (all walks of life are considered from bride to Buddhist monk to nurse) and gait – the now-familiar stagger now being the blueprint for the correct way for all animated corpses to adopt (until the remake in 2004, that is).

Buy Dawn of the Dead 4-disc DiviMax Special Edition: Amazon.com

To complement the garish visuals, Romero favoured library music, a technique he used to good effect in Night of the Living Dead. The De Wolfe library, still in regular use, was employed for this task and a variety of styles from the waltz muzak of the shopping centre to atmospheric electronic drones to a song by The Pretty Things, “I’m a Man”, a song co-written by one Peter Reno, better known as Mancunian zero-budget film legend, Cliff Twemlow and his working partner, Peter Taylor.

The most famous piece, unavailable until relatively recently, is The Gonk, by Harry Chappell, written in 1965. This trumpet/xylophone led polka-like march is deliciously out of place and yet completely in keeping with the absurdity of the situation. Argento’s vision of the film as a fast-paced action movie with geysers of blood throughout required a different approach and he used the Italian-based band Goblin (incorrectly credited as “The Goblins”) extensively. Goblin was a four-piece Italian/Brazilian band that did mostly contract work for film soundtracks. Argento, who received a credit for original music alongside Goblin, collaborated with the group to get songs for his cut of the film.

A completely different ending was originally planned and, rather like its predecessor, had a resolutely unhappy ending with Peter shooting himself and Fran either purposely or accidentally stepping into the helicopter blades, only for the blades to stop spinning at the conclusion to the end credits, an indicator that they were doomed anyway. These are both hinted at in the filmed version though all signs point to them being ultimately only existing on the page.

Recently, Romero has claimed that to be successful artistically, all horror films must be either political or satirical. Such a ludicrous statement may explain the director’s poor run of recent films but here it is rarely more apposite. The consumer-angle to the zombies mindless wandering is difficult to argue, though has now been stated so many times it’s in danger of overtaking the fact that the film is a magnificent piece of work; multi-layered in both character and plot (whatever became of the soldiers taking their boat down the river?) and influential to a generation of film-makers, as a horror film there are few better, a view echoed many, even the notoriously fickle Roger Ebert who gave it a great many thumbs up.

The film has also spawned a range of spoofs, copycat films, toys, games and merchandise. In 1985, Romero continued his zombie fascination with Day of the Dead and Dawn of the Dead was remade by Zack Snyder in 2004.

Daz Lawrence, MOVIES & MANIA

Other reviews:

” …the wildest, most deliriously exciting zombie flick of them all, and the movie which pretty much defines the concept of socially aware, politically astute horror cinema. Its influence has been felt in every zombie film since (and even on TV in ‘The Walking Dead’), and it remains a near-flawless piece of fist-pumping ultraviolence.” Time Out

Alternate versions and censorship issues:

Dawn of the Dead has received a number of re-cuts and re-edits, due mostly to Argento’s rights to edit the film for international foreign language release. Romero controlled the final cut of the film for English-language territories.

In addition, the film was edited further by censors or distributors in certain countries. Romero, acting as the editor for his film, completed a hasty 139-minute version of the film (now known as the Extended, or Director’s, Cut) for the premiere at the 1978 Cannes Film Festival. This was later pared down to 126 minutes for the U.S. theatrical release.

In the era before the NC-17 rating was available from the Motion Picture Association of America, the US theatrical cut of the film earned the taboo rating of X from the association because of its graphic violence. Rejecting this rating, Romero and the producers chose to release the film unrated so as to help the film’s commercial success. United Film Distribution Company eventually agreed to release it domestically in the United States. It eventually premiered in the US in New York City on April 20, 1979, fortunately beating Alien by a month.

The film was refused classification in Australia twice: in its theatrical release in 1978 and once again in 1979. The cuts presented to the Australian Classification Board were Argento’s cut and Romero’s cut, respectively. Dawn of the Dead was finally passed in the country cut with an R18+ rating in February 1980. It was banned in Queensland until at least 1986.

Dawn of the Dead was submitted to the BBFC in Britain for classification in June 1979 and was viewed by six examiners including the then Director of the BBFC, James Ferman.

BBFC examiners unanimously disliked the film, though acknowledged that the film did have its merits in terms of the film-making art. The main bone of contention was the zombies themselves – were they shells without feelings or dead people with families? One examiner felt so strongly that the film glorified violence that he excluded himself from any further screenings or discussions surrounding the work.

It was agreed that cuts to the film were necessary, Ferman as a self-appointed editor extraordinaire, stating that the film featured violence perpetrated against people which was “to a degree never before passed by the Board” and subsequently issued a cuts list that amounted to approximately 55 separate cuts (two minutes 17 seconds).

The following month a cut version of the film was re-submitted for re-examination and this time another team of examiners viewed the film. All of the examiners still disliked the film and some were convinced that cutting was not the solution to alleviating the possible desensitising effect that the film might have on vulnerable audiences. Despite this view, the suggestion of further extensive cuts was made and the film was once again seen by James Ferman, who subsequently issued a further one minute 29 seconds of cuts to more scenes of gory detail. At this point the distributor (Target International Pictures) was worried that the film would not be ready in time to be screened at the London Film Festival, so James Ferman suggested that the BBFC’s in-house editor create a version that would be acceptable within the guidelines of the X certificate.

In September 1979 Ferman wrote to the distributor exclaiming that “a tour de force of virtuoso editing has transformed this potential reject from a disgusting and desensitising wallow in the ghoulish details of violence and horror to a strong, but more conventional action piece… The cutting is not only skilful, but creative, and I think it has actually improved a number of the sequences by making the audience notice the emotions of the characters and the horror of the situation instead of being deadened by blood and gore”.

When the work was first submitted for classification for video in 1989 it arrived in its post-BBFC censored version, now clocking in at 120 minutes 20 seconds. However, under the Video Recordings Act 1984 (VRA), the film was to be subjected to another 12 seconds of cuts to scenes of zombie dismemberment and cannibalism. In 1997, Dawn of the Dead was picked up by a new distributor (BMG) who took the decision to submit the film in its original uncensored state, with a running time of 139 minutes.

This time the BBFC only insisted on six seconds of cuts. However, it was in 2003 that the film was finally passed at 18 uncut by the BBFC, with the examiners feeling that under the 2000 BBFC Guidelines it was impossible to justify cutting the work.

Internationally, Argento controlled the Euro cut for non-English speaking countries. The version he created clocked in at 119 minutes. It included changes such as more music from Goblin than the two cuts completed by Romero, removal of some expository scenes, and a faster cutting pace.

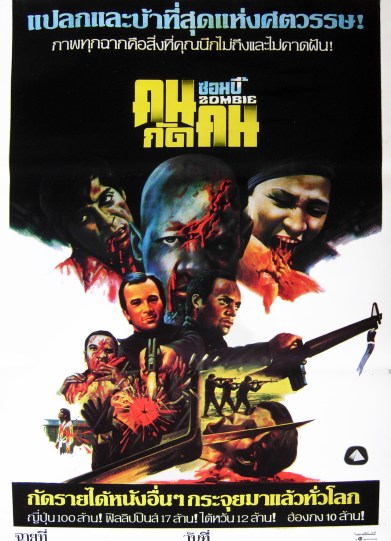

Released in Italy in September 1978, it actually debuted nearly nine months before the US theatrical cut. In Italy it was released under the full title Zombi: L’alba dei Morti Viventi, followed in March 1979 by France as Zombie: Le Crépuscule des Morts Vivants, in Spain as Zombi: El Regreso de los Muertos Vivientes, in the Netherlands as Zombie: In De Greep van de Zombies, by Germany’s Constantin Film as Zombie, and in Denmark as Zombie: Rædslernes Morgen.

Despite the various alternate versions of the film available, Dawn of the Dead was successful internationally. Its success in then-West Germany earned it the Golden Screen Award, given to films that have at least 3 million admissions within 18 months of release.

Buy Arrow Blu-ray: Amazon.co.uk

For YouTube content and more movie info click the page 2 link below