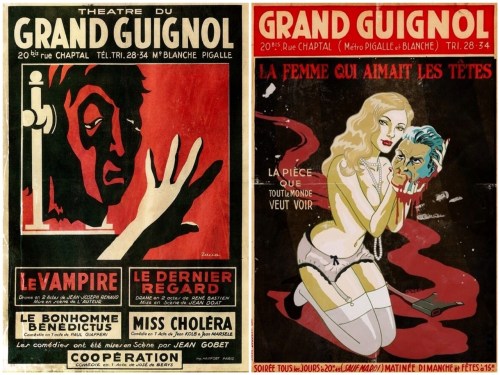

Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol [“The Theatre of the Big Puppet”] – known as the Grand Guignol – was a theatre in the Pigalle area of Paris (at 20 bis, rue Chaptal).

From its opening in 1897 until its closing in 1962, the theatre specialised in naturalistic, usually shocking, horror shows. Its name is often used as a general term for graphic, amoral horror entertainment, a genre popular from Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre (for instance Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, and Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi and The White Devil), to today’s splatter films. The influence has even spread to television shows such as Penny Dreadful.

Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol was founded in 1894 by the playwright and novelist, Oscar Méténier, who planned it as a space for naturalist performance. Méténier, who in his other job had been a chien de commisaire (a person who accompanied prisoners on a death row), created the theatre in a former chapel, the design keeping many of the original features, such as neo-Gothic wooden panelling, iron-barred boxes and two large angels positioned above the orchestra – the space was embellished with further Gothic adornments to create an atmosphere of unease and gloom.

With 293 seats, the venue was the smallest in Paris, the distance between the audience and actors being minimal and adding to the claustrophobic nature of the venue. The lack of space also influenced the productions themselves, the closeness of the audience meaning there was little point in attempting to create fantastical environments, the illusion shattered immediately by the actors breathing down their necks – not that there was any room on the 7-metres by 7-metre space for anything much in the way of backdrops.

The Guignol from which the theatre and movement took its name was originally a Mr Punch-like character who, in the relative safety of puppet form, commentated on social issues of the day. On occasion, so cutting were the views that Napoleon III’s police force were employed to ensure the rhetoric did not sway the masses. Initially, the theatre produced plays about a class of people who were not considered appropriate subjects in other venues: prostitutes, criminals, street urchins, con artists and others at the lower end of Paris society, all of whom spoke in the vernacular of the streets. Méténier’s plays were influenced by the likes of Maupassant and featured previously forbidden portrayals of whores and criminality as a way of life, prompting the police to temporarily close the theatre.

André de Lorde

By 1898, the theatre was already a huge success but it was also time for Méténier to stand to one side as artistic director, a place taken by Max Maurey, a relative unknown but one who had much experience in the world of theatre and public performance. Maurey saw his job to build on the reputation the theatre already had for boundary-pushing and take it to another level entirely. He saw the answer as horror, not just the tales of the supernatural but of the realistic, gory and terrifying re-enactments of brutality exacted on the actors, with such believability that many audience members took the plays as acts of torture and murder. Maurey judged the success of his shows by the number of audience members who fainted, a pretend doctor always on hand to add to the pretence.

The writer of the majority of the plays during this period was André de Latour (later de Lorde), spending his days as an unassuming librarian, his evenings writing upwards of 150 plays, all of them strewn with torture, murder and what we would now associate with splatter films. He often worked with the psychologist, Alfred Binet (the inventor of the I.Q. test) to ensure his depictions of madness (a common theme) were as accurate as possible.

Also crucial to the play’s success was the stage manager, Paul Ratineau, who, as part of his job, was responsible was the many gory special effects. This was some challenge, with the audience close enough to shake hands with the actors, Ratineau had to develop techniques from scratch, ensuring that not only were devices well-hidden but that the actors could employ them in a realistic manner, without detection. A local butcher supplied as much in the way of animal intestines as were required, whilst skilfully using lighting helped to make the scenes believable as well as aiding the sinister atmosphere.

Rubber appliances were made suitable for spewing innards when animals were not available and several concoctions were devised to simulate blood, ranging from cellulose solutions to red currant jelly. The actual beast’s eyeballs were coated in aspic to allow for re-use, and confectioner’s skills were employed to enable the eating of the orbs where required. Rubber tubes, bladders, fake blades and false limbs were also used to create gruesome scenes, though on occasion these did prove hazardous – reports detail instances where one actor was set on fire, one was nearly hanged and yet another was victim to some enthusiastic beating from her co-star, resulting in cuts, bruises and a nervous breakdown.

The actors themselves were not especially unusual – they were performers taking work wherever it came. There were a few stars of note – Paula Maxa (born Marie-Therese Beau) became known as “the Sarah Bernhardt of the impasse Chaptal” or, if you prefer, “the most assassinated woman in the world”, an appropriate claim for an actress who, during her career at the Grand Guignol, had her characters murdered more than 10,000 times in at least 60 different ways. Maxa was shot, scalped, strangled, disembowelled, flattened by a steamroller, guillotined, hanged, quartered, burned, cut apart with surgical tools and lancets, cut into eighty-three pieces by an invisible Spanish dagger, had her innards stolen, stung by a scorpion, poisoned with arsenic, devoured by a puma, strangled by a pearl necklace, crucified and whipped; she was also put to sleep by a bouquet of roses and kissed by a leper, amongst other treats.

Another actor, L.Paulais (real name, Georges) portrayed both victim and villain with equal skill and opposite Maxa in every one of their many performances. He once commented that the secret to the realistic performances was their shared fear. The actress Rafaela Ottiano was one of the few, perhaps even only, original actors in the theatre to transfer to the Big Screen, appearing in Tod Browning’s Devil Doll (1936).

At the Grand Guignol, patrons would see five or six plays, all in a style that attempted to be brutally true to the theatre’s naturalistic ideals. These plays often explored the altered states, like insanity, hypnosis, panic, under which uncontrolled horror could happen. Some of the horrors came from the nature of the crimes shown, which often had very little reason behind them and in which the evildoers were rarely punished or defeated. To heighten the effect, horror plays were often alternated with comedies.

Under the new theatre director, Camille Choisy, special effects continued to be an important part of the performances. Many of the attendees would barely be able to control themselves – if they weren’t fainting, they were quite possibly reaching something approaching orgasmic fervour, private booths being extremely popular to allow some privacy for their heightened emotions. On occasion, the actors were forced to come out of character to reprimand more excitable audience members. Some particularly salacious examples of plays performed include:

Le Laboratoire des Hallucinations, by André de Lorde: When a doctor finds his wife’s lover in his operating room, he performs a graphic brain surgery rendering the adulterer a hallucinating semi-zombie. Now insane, the lover/patient hammers a chisel into the doctor’s brain.

Un Crime dans une Maison de Fous, by André de Lorde: Two hags in an insane asylum use scissors to blind a young, pretty fellow inmate out of jealousy.

L’Horrible Passion, by André de Lorde: A nanny strangles the children in her care.

Le Baiser dans la nuit by Maurice Level: A young woman visits the man whose face she horribly disfigured with acid, where he obtains his revenge.

Jack Jouvin served as director from 1930 to 1937. He shifted the theatre’s subject matter, focusing performances not on gory horror but psychological drama. Under his leadership the theatre’s popularity waned; and after World War II, it was not well-attended. Grand Guignol flourished briefly in London in the early 1920s under the direction of Jose Levy, where it attracted the talents of Sybil Thorndike and Noël Coward, and a series of short English “Grand Guignol” films (using original screenplays, not play adaptations) was made at the same time, directed by Fred Paul. Meanwhile, in France, audiences had sunk to such low numbers that the theatre had no option but to close its doors in 1962. The building still remains but is used by a theatre group performing plays in sign language. Modern revivals in the tradition of Grand Guignol have surfaced both in England and in America.

Grand Guignol was hugely influential on film-making both in subject and style. Obvious examples include Prince of Terror De Lorde’s works being used as the basis for D.W. Griffith’s Lonely Villa (1909), Maurice Tourneur’s The Lunatics (1913) and Jean Renoir’s Diary of a Chambermaid (1946). Others clearly influenced include the Peter Lorre-starring Mad Love (1935), Samuel Gallu’s Theatre of Death (1967), H.G. Lewis’ Wizard of Gore (1970) and Joel M. Reed’s notorious Blood Sucking Freaks (1975).

More recently, More recently, Grand Guignol has featured in the hit television series, Penny Dreadful. The 1963 mondo film Ecco includes a scene which may have been filmed at the Grand Guignol theatre during its final years – as such, it would be the only footage known to exist.

Daz Lawrence, MOVIES & MANIA

We are grateful to Life Magazine for some images and Grand Guignol website for some of the information.